By Rasheedat Oladotun-Iliyas

(Photo: SIM cards and handcuffs. Image credit: AI)

In 2025, Abimbola Tijani registered a new SIM card, linked it to her National Identification Number (NIN) in compliance with the Federal Government’s directive, and handed it over to her 14-year-old son to ease communication while she was away.

However, her son soon became inundated with bank alerts meant for a stranger, calls and text messages followed, some personal, others financial.

“I did not know what to do,” Abimbola recounted. “I have been hearing stories of how people get arrested for using phone numbers belonging to kidnappers. I had to retrieve the SIM card from him and abandon it.”

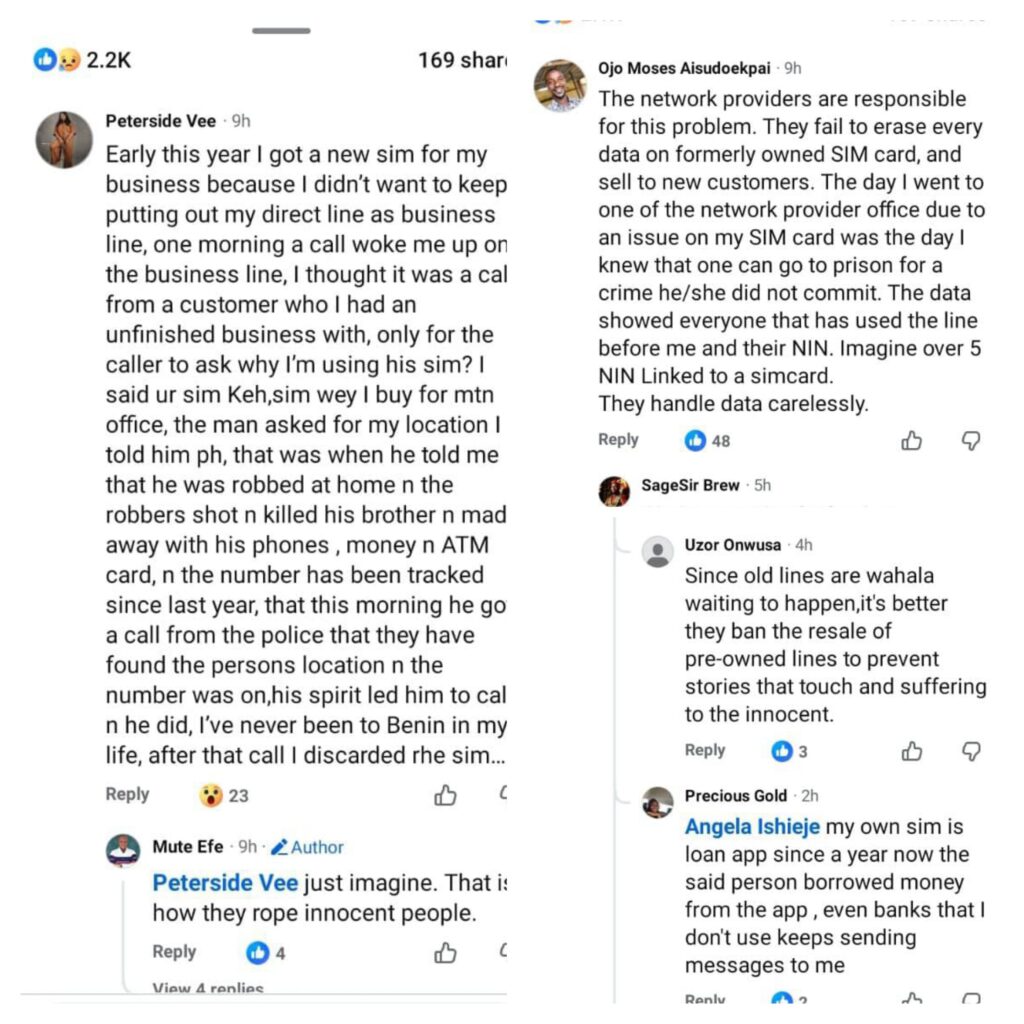

Abimbola’s story is not isolated. Across Nigeria, new SIM owners routinely inherit the digital ghosts of previous users, bank alerts, loan reminders, debt recovery calls, social media verification codes, and sometimes, far more troubling associations. Most victims quietly block the calls or discard the SIM. A few have not been so lucky.

In December 2025, an Instagram post drew attention to a troubling arrest. A young woman narrated how her father, an Ekiti-based man, was allegedly detained by security operatives for using a mobile number previously linked to kidnappers. According to the account, he had purchased the mobile SIM while visiting her in Lagos, and it was duly registered in his name.

The case, reported by Sahara Reporters, sparked public outrage. Nigerians flooded the comment section with similar stories of inheriting phone numbers with troubling histories. Some of them recounted receiving bank alerts meant for strangers, calls from unknown contacts, and in extreme cases, police detention. Many of them questioned why security agencies often arrest first, without verifying whether a SIM card has been recycled.

Earlier cases had already set precedent. Mariam Ibrahim, a National Youth Service Corps (NYSC) member, was detained after her phone number was linked to kidnapping suspects. The telecom provider later confirmed the number had been reassigned months after the alleged crime.

In 2020, Anthony Okolie spent ten weeks in detention after receiving a recycled number previously used by a relative of the then-President Muhammadu Buhari. He was eventually released when the complainant failed to appear.

In response to the detention of Mariam, the Force Public Relations Officer, Benjamin Hundeyin, had confirmed that the person being arrested also needed to prove their innocence to law enforcement officers.

“The only thing we can call wrong in this is if the policemen still hold on to her even after Airtel has proven that she brought it after the kidnapping incident. So, my advice is, have evidence of all your purchases and prove the date you bought the SIM,” Hundeyin said.

These incidents expose a growing fault line in Nigeria’s digital public infrastructure ecosystem. Phone numbers are often treated by law enforcement as permanent identifiers, even though they are routinely recycled.

Mobile numbers an identity anchor in a digital economy

In today’s digital economy, a phone number is no longer just a means of communication, it has become an identity anchor- linking an individual to other digital identities in Nigeria’s emerging Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI).

From banking to healthcare, education to government benefits, access increasingly depends on an active mobile line. Even the National Identification Number (NIN) and Bank Verification Number (BVN) systems depend on linked phone numbers for verification and retrieval through USSD codes.

Mobile numbers now connect individuals to: Bank accounts and mobile money wallets, loan and fintech platforms, email recovery systems, social media verification, one-time passwords (OTPs) for financial transactions and government services.

In effect, phone numbers have become digital identity anchors.

Yet unlike the NIN which is the foundational identity in Nigeria’s DPI, which is permanent and never reassigned even after death, phone numbers can be temporary because they can be abandoned, disconnected, and reassigned to new users.

This contradiction lies at the heart of the problem.

When subscribers discard SIM cards without delinking them from digital services, they expose themselves and future users to identity theft, financial fraud, and legal trouble.

A student, Muhammed Salahu, recounted how he had to visit the MTN customer service office to complain about the strange calls on his newly registered SIM card. “I kept explaining that I am now the new owner of the phone number, but they will want to engage me in conversations I know nothing about,” Muhammad recounted.

Why telecom operators recycle numbers

Mobile numbers, short codes, and other numbering assets, form the foundation of today’s telecommunications system. Globally, their administration is guided by the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) through Recommendation E.164, a framework designed to promote orderly management, efficiency, and fair access to numbering resources across countries.

In Nigeria, the Nigerian Communications Commission (NCC), under the Nigerian Communications Act 2003 and the National Numbering Plan, allocates numbering blocks to licensed operators such as MTN, Airtel, Globacom, and 9mobile.

Under NCC regulations, a mobile line may be recycled after 180 days of inactivity. A number is considered dormant if it records no revenue-yielding activity, no outgoing or incoming calls, SMS, billable USSD, or data usage.

In a reaction to concerns about number recycling, the NCC affirmed that numbering resources are limited by nature because every telephone number must follow a prescribed structure and specific digit length, therefore, the total pool of possible combinations is restricted.

For telecom operators, dormant lines represent both revenue loss and shrinking market share. Recycling restores the number to the pool. But once reassigned, the old subscriber cannot reclaim it.

As of December 2025, the total number of active telecommunications subscribers across all networks in Nigeria stood at 179.64 million. The top three operators were MTN Nigeria with 51.87% market share; followed by Airtel Nigeria with a subscriber base of 33.94% of the market share; while Globacom had 12.39%.

A 2022 report by Nairametrics put the number of inactive phone numbers at 103.3 million across MTN, Airtel, Globacom and 9mobile. This left the operators with only 67% revenue generation from their customer base. In February 2023, Nigeria had about 323.6 million connected lines across MTN, Glo, Airtel, and 9mobile, but only 226.8 million were active. At one point, unused lines exceeded 105 million.

As of February 28, 2024, the NCC threatened to deactivate 45 million inactive mobile numbers. 42 million of the numbers were said to have been dormant for over one year, while 3 million others were yet to link their NIN to their numbers.

As a safeguard, NCC permits recycling after inactivity, provided previous NIN links are removed. However, critics say this safeguard is outdated. According to them, in today’s digital ecosystem, phone numbers are linked to far more identifiers than NINs. They are connected to bank accounts, mobile money wallets, loan platforms, social media profiles, email services, and government records. Hence, removing a NIN link does not erase these associations. As a result, recycled numbers often carry residual digital footprints, exposing both old and new users to fraud and suspicion.

Observers blamed the number of inactive mobile numbers on factors which includes competition for market share by the Mobile Network Operators (MNOs).

When mobile telephony gained popularity in Nigeria in 2001, SIM cards were expensive, selling for as much as ₦60,000. This limited SIM card number ownership to few people who could afford it at that time. But the sector was soon liberalised, giving room for a sharp fall in prices of SIM card numbers. At some points, SIM cards were given free or bundled in promotions with free bandwidth and airtime upon activation.

Today, they cost less than ₦1,000 at accredited outlets.

This affordability encourages multiple SIM card ownership and casual abandonment. The introduction of compulsory NIN–SIM linkage in 2020 by the Federal government, alongside limit on mobile number ownership per operator, further pushed many users to discard extra mobile lines.

The criminal justice trap

Legal experts argue that the real danger emerges when law enforcement agencies fail to verify the lifecycle of a mobile number before making arrests.

Hundeyin, the Police Force Public Relations Officer, once stated that individuals must provide proof of purchase to establish innocence if implicated through a phone number. However, lawyers counter that the burden of proof lies with the prosecution.

Speaking on the issue, a lawyer, Barnabas Hunjo, insists that telecom operators maintain digital records, including biometric data captured during SIM registration.

“There is a burden of proof on the prosecution, that is the police, to dig further,” he explained. To try to know at what point did the person arrested started using the SIM card.”

Hunjo noted that “those records will be with the telecom operator. Remember registration of SIM cards go with the NIN, and they are digital footprints. The biometrics will be captured – fingerprints and face of the subscriber. These are data the telecom provider will have. A further investigation will save everybody the problem.”

He also advised people who misplaced their SIM cards should not just ignore but ensure retrieval to avoid it falling into wrong hands.

Also, in a 2025 study, a researcher, Testimony Akinkunmi warned that SIM recycling exposes bank accounts to unauthorised USSD access and identity theft, hence the need for harmonised regulation, enhanced safeguards, and stronger consumer awareness.

Although the problem arising from mobile number recycling is not unique to Nigeria, stakeholders opined that efforts must be made to address identified challenges to ensure accurate and proper data alignment across digital platforms.

IT experts also advise people to set email addresses for two step verification and authentication to avoid exposing their identities to new users.

The plan by the NCC to improve its Telecom Identity Risk Management Policy, (TIRMP) is expected to help curb fraudulent activities, improve data sharing amongst relevant agencies and strengthen trust in digital as well as financial transactions.

This report is produced under the DPI Africa Journalism Fellowship Programme of the Media Foundation for West Africa and Co-Develop.