By Bilkis Abdulraheem Lawal

In 2014, a seven-month pregnant Cameroonian woman who arrived at the Durumi Internally Displaced Persons Camp in Abuja’s Federal Capital Territory (FCT) after trekking for about two weeks died because she was reportedly denied delivery care at a government Hospital in Abuja.

When she went into labour and was rushed to the hospital, she was allegedly asked to pay N200,000 for surgery which she could not afford.

“I told them we were IDPs and had no money,” Ilyatu Ayuba, the woman leader for Durumi Area 1 and the coordinator of women leaders across 18 IDP camps in the FCT recalled. “I begged them to save her life while we looked for help, but they refused.”

The woman died during the argument. The baby was delivered without medical assistance, but according to Ayuba, the hospital staff declined to care for the newborn, who also died shortly after.

“They asked me to pay ₦150,000 to collect the bodies,” she said. “If I had that money, I would have paid it earlier to save both mother and child.”

The bodies of the mother and baby were only retrieved and buried after a note was taken to the social welfare.

“That day, I prayed to God and promised to start delivering pregnant women here, because I lived with my grandmother, who was a traditional birth attendant,” Ayuba said.

The late mother and her baby are among victims of the lack of needed government presence at the IDP camp where about 3,500 displaced people face heightened risks to maternal and child health, disease outbreaks and a future stripped of educational opportunity.

According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) June 2025 situation report, Nigeria hosts approximately 8.18 million internally displaced persons (IDPs), the highest figure in West Africa. Many live in temporary settlements without access to basic services, in conditions that fall far below minimum humanitarian standards. The numbers continue to grow.

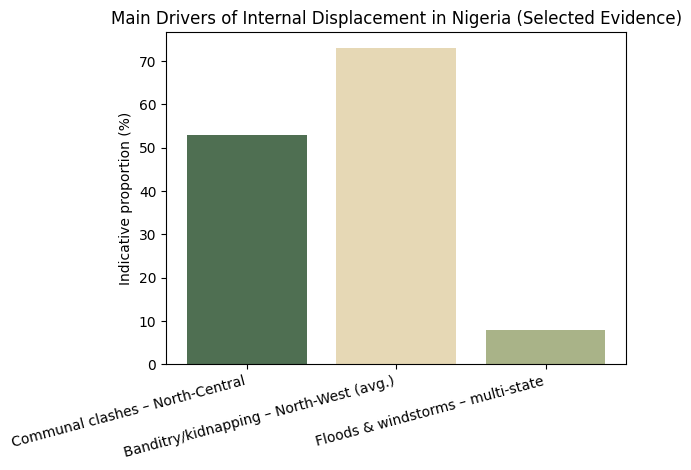

The reasons for displacement vary across Nigeria. According to the International Organisation for Migration, (IOM), in the North-Central region, communal clashes account for up to 53 per cent of displacement in states such as Benue, Nasarawa and Plateau. In the North-West, armed banditry and kidnapping dominate, with Sokoto recording 81 per cent, Zamfara 79 per cent, Katsina 77 per cent, and Kaduna 55 per cent of displacement linked to such violence. Floods and windstorms have also displaced communities in at least eight states.

Ayuba, who said she arrived at Durumi camp on 11 February 2011, becoming its first resident after her husband, a Nigerian soldier, was killed by Boko Haram in Borno State in 2011 and her third child stepped on an explosive device, sustaining severe injuries that kept him in hospital for two years, has since the tragic death of the mother and child been offering free traditional delivery.

Relying on her experience with her grandmother and herbal knowledge, along with another woman she trained in 2019 Hadiza, who assisted her until her death a few weeks ago, she has delivered 228 babies, including a set of triplets, without collecting a dime.

Ayuba said she recently assisted in the delivery of a baby born with ambiguous genitalia, noting that the child has been referred to a hospital while the family is seeking funds for corrective surgery.

An individual donated a container, which Ayuba now uses as a makeshift consultation and delivery room. She lamented neglect from the government. “Are we not Nigerians too? We have been abandoned.”

Giving Birth Without Care

Nigeria currently ranks as the country with the second-highest number of maternal deaths globally, according to the World Health Organization (WHO) 2023 report, with a maternal mortality ratio of 1,047 deaths per 100,000 live births.

For women in Durumi camp, these statistics translate into lived danger.

Hannah Abel, displaced from Borno State, has spent three years in the camp. She attended antenatal care at the Area 2 Primary Healthcare Centre because it was free, but went into labour at night with no transport available.

“It was the woman leader who delivered me,” she said.

“I want the government to consider we IDPs, we find it difficult during childbirth because there is no drug or equipment in the clinic,” she said.

Hannah now cleans houses to survive and cares for her one-year-old child. She urged the government to equip the camp clinic.

Another nursing mother, Sarah from Plateau State, said she delivered at Redeem Hospital, Area 1, paying ₦35,000.

“I did not do my antenatal in the camp clinic because some of the things pregnant women need are not available in the clinic. “There is no nurse, no drugs or necessary equipment.”

Education in a Place of Trauma

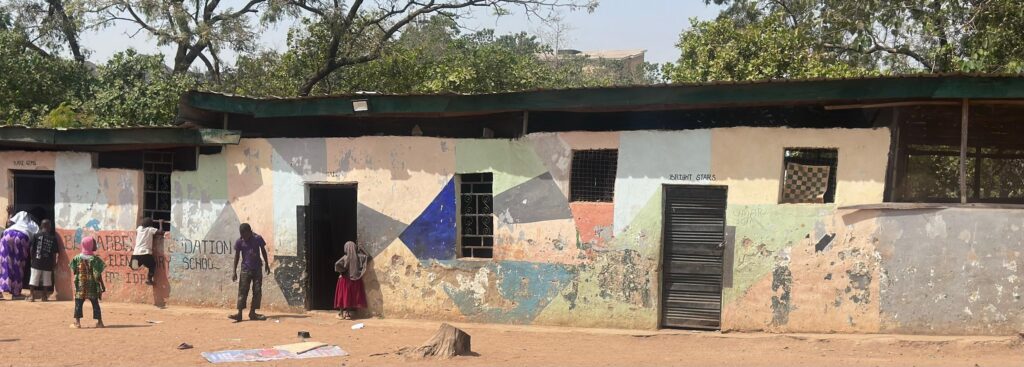

While healthcare remains fragile, education at Durumi camp survives largely through the intervention of African Arise International, a non-governmental organisation running a makeshift school inside the settlement.

Issa Bello, a staff member of the organisation, said he first arrived at the camp during his National Youth Service year but chose to remain after witnessing the realities facing displaced children.

“Nobody wishes bad things for themselves,” Bello said. “Some of these children lived comfortable lives before insurgency destroyed everything. This is not the life they chose.”

The organisation currently provides nursery and primary education, focusing on literacy and numeracy to give children a foundation for future learning.

“At the grassroots level, education is everything,” Bello said. “Without a solid foundation, there is no way forward.”

He said teaching often requires improvisation due to limited infrastructure.

“There were times I had to teach mathematics in the Hausa language, just to make sure they understood,” he said.

Beyond teaching, Bello said the foundation feeds the children once a week and he also contributes his personal money sometimes to providing food and basic learning materials to encourage attendance.

“At least once a week, we feed the children,” he said. “Sometimes, that is the motivation they need to come to school.”

He urged the government to recognise the camp officially.

“If the government acknowledges that IDPs live here, help will come,” Bello said. “People want to help, but they need visibility.”

He added that political interest in the camp surfaces mainly during elections.

“They remember them when it is time to register for PVCs,” he said. “After that, they disappear.”

On the future of children who complete primary education, Bello admitted uncertainty.

“Most parents cannot afford secondary school,” he said. “That is why we are planning to establish a secondary school and vocational training centre, so these children can gain skills and dignity.”

Elizabeth Saliu, one of the women in the camp explained that her first and second children, who should be in secondary school, are currently out of school due to a lack of funds.

“My first child now makes hair for people to support the family,” she said, adding that her last-born is enrolled in the free education programme provided by African Arise International within the camp.

Recently, EmpowerHer Health Fellows of Women in Global Health Nigeria paid a humanitarian visit to the camp, engaging teenage girls who, despite deep uncertainty, continue to nurture dreams of a better future.

No Toilets, No Safety

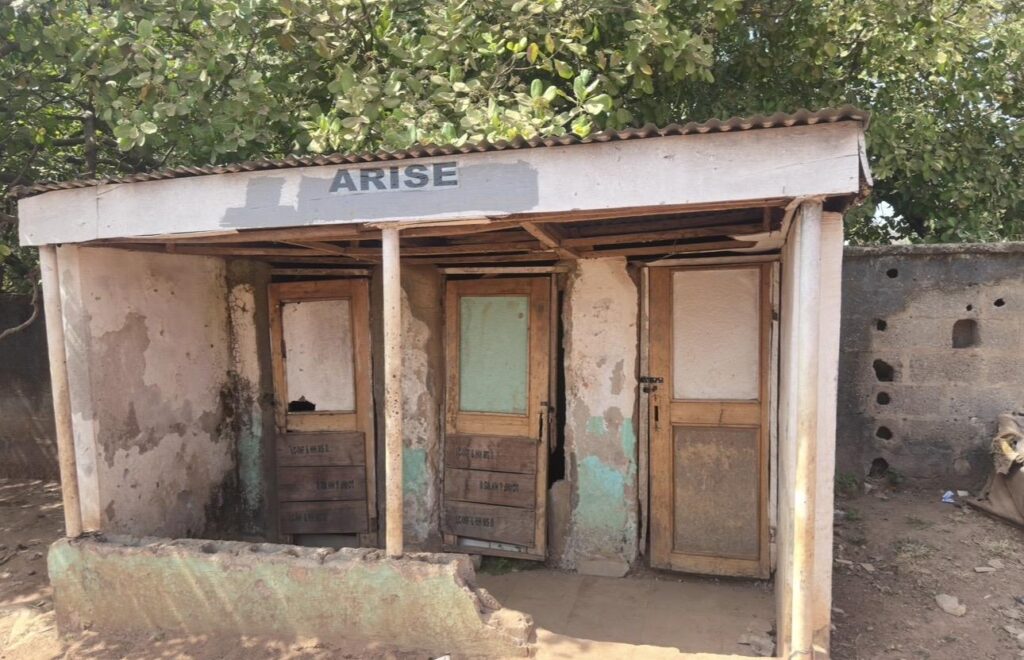

Beyond education and healthcare, Durumi camp faces a severe water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) crisis.

The camp has no functional toilets, apart from three toilets the school run by African Arise International use for the pupils. Residents practise open defecation, often in areas where children play, eat and scavenge.

Medical Warnings: “A Catastrophic Risk”

Dr Amina Mohammed Hassan, Medical Director of King Fahad ibn AbdulAziz Women and Children’s hospital, Gusau, Zamfara State, warned that conditions in many IDP camps pose grave risks to maternal and child health.

“Water, sanitation and hygiene are central to disease prevention,” she said. “In IDP camps, we commonly see diseases linked to water scarcity and stagnant water.”

She explained that poor hygiene and scarcity of water accelerate the spread of cholera, diarrhoeal diseases, scabies and skin infections, while open defecation attracts disease-carrying flies, rodents and cockroaches, increasing the risk of outbreaks such as Lassa fever.

On maternal health, Dr Hassan was unequivocal.

“The greatest factor in reducing maternal and newborn deaths is having a skilled birth attendant at every delivery,” she said. “Without that, the risks are enormous.”

She listed possible complications including prolonged labour, uterine rupture, postpartum haemorrhage, sepsis and birth asphyxia, noting that the first 24 hours after childbirth are critical.

“There is no equipment to monitor labour or resuscitate newborns,” she said. “If a baby is born not breathing, survival is unlikely.”

Dr Hassan stressed that IDPs qualify as extremely vulnerable populations and should be enrolled in the Basic Healthcare Provision Fund, which provides free services for pregnant women, children under five, the elderly and the poorest households.

“There are existing programmes that can help,” she said. “For example, the Comprehensive Emergency Obstetric and Newborn Care initiative allows facilities to conduct life-saving surgeries and receive reimbursement through the National Health Insurance Authority.”

She also highlighted the importance of psychosocial and mental health support, warning that untreated trauma can lead to depression, post-traumatic stress disorder and long-term behavioural consequences.

“Trauma does not heal on its own,” she said. “Support is essential.”

While donations from well-meaning Nigerians and non-governmental organisations provide temporary relief, stakeholders say they cannot replace the role of the government. They argue that access to basic services such as clean water, sanitation, healthcare and education are essential for displaced people to rebuild their lives, particularly children whose schooling and development have been disrupted. They urged the government at all levels to find a sustainable solution for IDPs.

End