By Rasheedat Oladotun-Iliyas

As Nigeria deepens its transition to Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI) for financial services, one critical gap persists: accessibility. Across major cities and rural towns, many Automated Teller Machines (ATMs) lack basic voice prompts or audio navigation features, making it impossible for visually impaired and non-literate users to carry out self-service transactions. Instead, they are forced to rely on strangers or family members putting their privacy, financial security, and autonomy at risk.

The problem extends beyond audio support. Many ATMs are installed in locations that physically exclude wheelchair users, while entrances to banking halls often lack ramps or accessible pathways. Correspondent Rasheedat Oladotun-Iliyas reports that urgent measures need to be taken to enable millions of Nigerians with disabilities equal access to essential financial services.

“That thing (accessibility) is killing. “It’s like a pandemic for the community of persons with disabilities,” says Ibrahim Muftau Oleshin, the Chairman, National Association of Persons With Physical Disabilities, Kwara State Chapter.

He explains that many members of the association remain excluded from the financial system.

“We have many members who do not have NIN, bank accounts because of accessibility, because of stress, because of the discrimination.

“There was a time when the Federal Government was doing empowerment, and giving grants to persons with disabilities, but is it not someone with account details that we will submit? When we ask them to go and get their NIN, open a bank account, they will tell you, when we get to the bank, how are we going to cope? Who is going to assist us?” Ibrahim Muftau Oleshin explains.

Oleshin is the Chairman, National Association of Persons With Physical Disabilities, Kwara State Chapter and also doubles as the Special Assistant on Special Needs to the Ilorin East Local Government Chairman.

He says the inability of his members to have unfettered access into the banking hall and ATM pavilions leaves them out of financial inclusion. He describes the hurdles his members face from commuting from home to the bank, to navigating banking spaces, as traumatic, noting that accessing bank services itself is another hurdle.

“The stress is much. To enter a vehicle, they (commercial vehicle operators) charge us what they charge for carrying a corpse to discourage us from boarding. They don’t want to render any assistance. All these discourage my members from even leaving their comfort zone. Our accessibility is denied.”

He further explains that for people using crutches and walking sticks like himself, the banks most times turn off the door security alarm for them to get in, while people on wheelchairs have to crawl in because the electronic door is not spacious enough to accommodate their wheelchairs.

“That thing is killing. It’s like a pandemic for the community of persons with disabilities,” he notes sighing.

“We have a slogan, “ Don’t pity us,” instead do the necessary things. It’s disheartening. We have been making advocacy visits to some of the banks. They promised to make adjustments.”

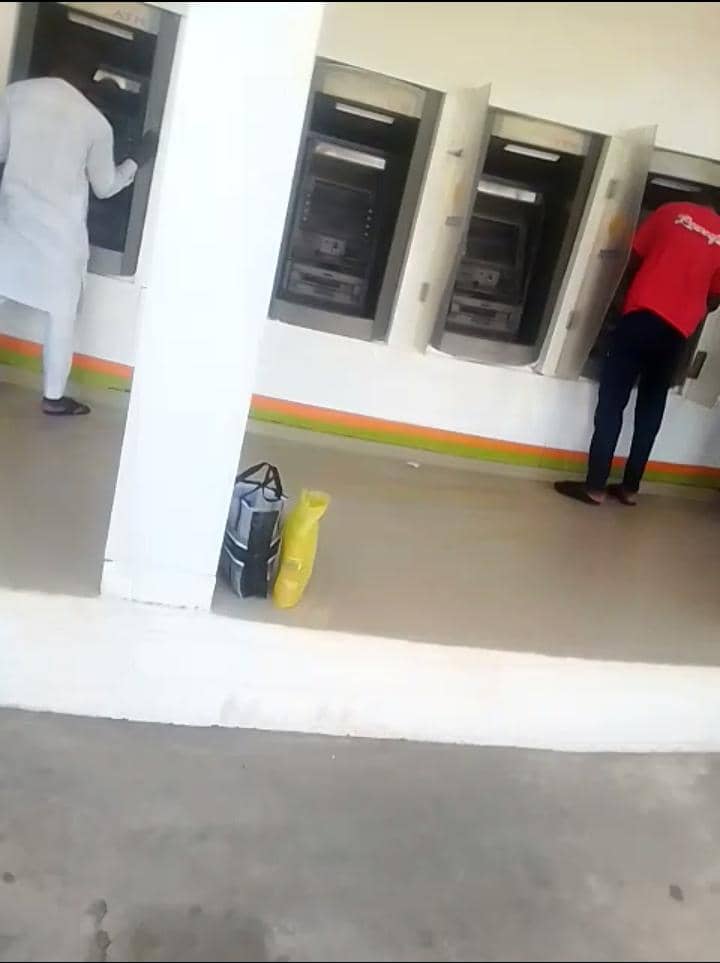

Our correspondent visited some banks along A Division to Post Office and Unity Road in the Ilorin metropolis and finds that out of 10 banks visited, only two made provision for ramps. However, the narrow pathways through the electronic doors at most of the entrances still stand as a barrier. It was also observed that the ATM galleries were not built with persons with disabilities in mind.

“When I go to the bank and I try to pass through the electronic door, it begins to make noise. They have to turn off the computer to enable me to pass through with my white cane,” said Femi Anpitan, a teacher at the Kwara State School for Special Needs who shared his experiences on accessibility and inclusion in banking operations.

“They will ask me, “Why did you come alone?” I will respond, “I don’t have a child and people that can help me have gone to school” And then, they would say “Just wait, we will look for somebody to assist you.

“Accessing the bank is always an issue. Going through the staircase is another stress,” Anpitan, who is visually impaired notes.

Akeem Lawal, who is also visually impaired explains that in one instance he was made to leave behind a guard cane at the bank entrance. Leaving him stumbling in the bank hall.

“Many of the banks used to harass us if we went without a human guide,” he says. “Without the guard cane, it makes it difficult to navigate the banking hall especially when one is alone.”

Navigating Inaccessible ATM Galleries and Expired ATM Cards

Like Anpitan, Oleshin, and Lawal, many persons with disabilities have much to say about their exclusion. From inaccessible banking halls and ATM galleries, and having to get an indemnity form from the High Court for ATM renewal, particularly for persons with visual impairment, all seem to scream “unwanted”

Isiaka Ajala, a member of National Association for the Blind, Kwara, operates two bank accounts with expired ATM cards. He says he is unhappy that he has to get an indemnity form to renew them.

“Am I not old enough to use an ATM card?, he asks. “I have been using the card since 2022.”

A 200 – level student of University of Ilorin, Department of Social Works, Shukura Abdulganiyu says the process of replacing her broken ATM has left her without one.

“They said I need the indemnity form so that they will not be liable for whatever happens to my money. But the stress of going to High Court to get it has made me stay back.”

The indemnity form or court affidavit absorb the banks of any liability or fraud in.case of any issues with the ATM transactions. It shifts the entire risk to the visually impaired customer. It has been termed discriminatory because same is not required from a sighted customer requiring card renewal.

Aside from accessibility to the ATM gallery, Lawal – Chairman, National Association for the Blind, Kwara State Chapter – says most ATMs used by Nigerian banks are obsolete in other countries because they lack accessibility standards for PWDs.

“Findings from our friends there (foreign countries) showed that they have ATMs that provide audio services to persons with visual impairments. You do not need to call on someone before you can make use of it. We have some with embossed signs, that is braille. We have some of them here in Nigeria, but it’s not enough to have an ATM keypad with braille dots because you still need to know what is on the screen.

“You might have been able to press the numbers, but what about the next instruction, the information on the screen? The only information it gives you is at the beginning, “Pls, insert your card.” And then, “Enter your secret number.” And that is where the whole instruction stops. And it ought to take you through the process from the beginning to the end of the transaction.”

Abdulganiyu, the student from the department of social works and Maryam Abdulsalam both agree that TalkBack enabled ATMs would allow them transact independently without exposing their financial details to anyone.

“It will be better and make our transactions confidential. We have a TalkBack app on our android phones that helps us make use of it.

“Talkback on every ATM and POS will make it easy. Last week, I wanted to make a transaction, and the woman handed me the POS to punch in my password. But I was unable to because it has no TalkBack,” Abdulsalam recalls.

Ruth Obebe, also visually impaired, says she is selective about the bank she uses to avoid embarrassment, while noting that she relied on her younger brother to make transactions.

“It will be very good. I will really appreciate it . When I’m doing things independently, I always love it, rather than depend on someone,” she says.

Ibrahim Adeniyi with visual impairment, says he prefers to use Fintech rather than a commercial bank. With the TalkBack app on his mobile phone, he is able to navigate transactions independently. He believes having similar software on ATMs at banks will protect people from being defrauded.

For many unbanked persons with disabilities, the alternative is using family members accounts for transactions, which sometimes exposes them to extortion.

Between Regulatory Frameworks, Implementation and Monitoring

The UN SG report 2024 states that 25 per cent of banks and ATMs in developed regions of the world and 50 per cent in developing regions, are inaccessible to persons with disabilities, particularly those on wheelchairs. Similarly, the World Bank Group’s Global Findex Database 2025 reports that 1.3 billion adults still do not have bank accounts. This number undoubtedly includes persons with disabilities who lack access to banking halls, ATM galleries and do not find it easy to renew their ATM cards.

The excitement that greeted the passage of the Discrimination Against Persons With Disabilities (Prohibition) Act by the Buhari Administration in 2018 has waned down as beneficiaries struggle to see its benefits. Despite the existence of the National Commission for Persons With Disabilities, NCPWD, responsible for the enforcement of the law, many public buildings, including banks, continue to flout the law, an outcome observers describe as a failure of regulatory agencies in charge of monitoring, evaluation and implementation.

The Act mandates that all public buildings be accessible to persons with disabilities with the construction of ramps. Older buildings are required to comply within five years of enactment of the law. However, seven years on, many banks and ATMs remain inaccessible to persons with disabilities.

During the visit to the banks in the Ilorin metropolis, a security man at the entrance of one of the banks told the reporter that a bank official might have to come out to attend to a customer using a wheelchair. His response shows that the bank hardly has wheelchair users coming for bank transactions.

“If he cannot enter, we will ask one of the staff to come and attend to the customer outside. And if it is compulsory for him to go into the banking hall, we will find a way for him to enter.”

Often, that “way” involves going through the backdoor staff entrances or being carried or crawling through the electronic door.

Nigeria launched its Digital Public Infrastructure, DPI, framework in March 2025, followed by the inauguration of the Presidential Committee on Implementation of DPI in May 2025 and its announcement as a member of the Digital Public Goods Alliance. As the National Information Technology Development Agency (NITDA) set out to unify digital payment systems, digital identity and data by the first quarter of 2026, rights advocates like Kazeem Lawal, hope that the concerns of persons with disabilities would be given adequate attention. He explains that as a result of accessibility and discrimination, many people with disabilities are unbanked and are therefore cut off from some essential services, government grants, loans and other finances. “The building itself must be accessible. They should have tactile description on their walls right from their gate to guide visually impaired persons through the banking hall. Basic accessibility standards should be built on bank websites and apps. For those on wheelchairs, there should be ramps.

“About three years ago, we embarked on minimum accessibility standards for buildings and structures, approved by the Federal Executive Council. Those details in the document should be followed on size of the doors, elevators etc.”

According to Razak Adekoya, a disability inclusion specialist, asking a person with visual disability to get an indemnity form for ATM card renewal from High Court while their sighted counterparts simply complete a form in the banking hall, is in itself, discrimination.

“…that people with disabilities cannot manage their finances independently-traps them in a cycle of exclusion and dependence.” He maintains that the financial sector stands to gain economically and ethically by actively banking Nigeria’s estimated 5.1 million adults with disabilities.

He recommends adapting inclusive disability ecosystems from Kenya and South Africa and urges the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) to update the National Financial Inclusion Strategy to meet the specific needs of PWDs.

“We are working with CBN to ensure that all commercial banks in Nigeria have access to PWDs,” says Bitrus Dako, Director Accessibility, NCPWD, Abuja

The National Commission for Persons With Disabilities, NCPWD, is an agency of the Federal Government charged with the mandate to ensure full compliance with the provisions of Discrimination Against Persons With Disabilities (Prohibition) Act, 2018. On its official website, the Commission prides itself as “An institution working to promote an inclusive society for persons with disabilities through research, advocacy, engagement, mainstreaming, policy development, and enforcement.” Some of its core values are non-discrimination, accessibility, equity and accountability.

Despite criticisms, the Director, Accessibility, NCPWD, Abuja, Mr Bitrus Sule Dako says the Commission has made tremendous efforts in ensuring compliance and is developing a guideline to ensure enforcement. “We are working with CBN to ensure that all commercial banks in Nigeria have access to PWDs. So, by the time the Commission finishes engaging with the Central Bank and has a Memorandum Of Understanding, they will direct all the banks to ensure compliance.”

Dako who also emphasizes the role of the National Orientation Agency, NOA in sensitization of the public on accessibility, said that the regulation will be fully enforced soon. “An ignorance of the law is not an excuse,” he maintains.

—————————————————————-

This report is produced under the DPI Africa Journalism Fellowship Programme of the Media Foundation for West Africa and Co-Develop.