By Alfred Ajayi

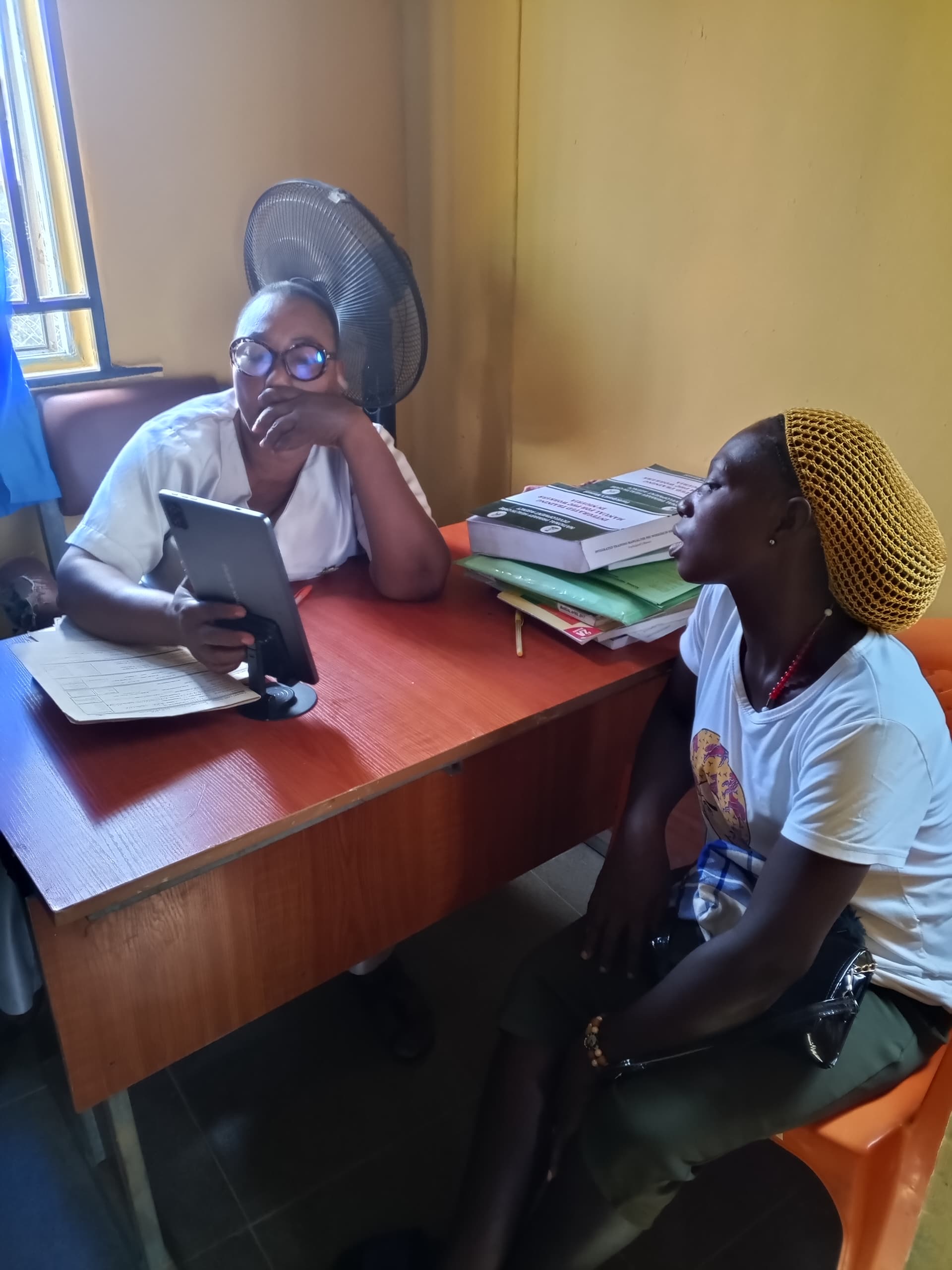

On a December evening in Umudora, a farming community in Anambra West Local Government Area, LGA, a primary healthcare worker stood beside a patient, clutching a device that refused to work. The telemedicine tablet on her desk was meant to link her to a doctor miles away. Instead, it stared back at her, useless. There was no network. As minutes slipped by and the patient’s condition worsened, she reached for her personal phone, swapping SIM cards one after the other, hoping one would catch a signal before time ran out.

Stella Ogolor, the Officer in Charge, OIC of the Umudora Primary Healthcare Centre (PHC), said such moments have become routine. The facility, she explained, rarely uses the telemedicine device because mobile network coverage is unreliable in the area. In urgent cases, health workers fall back on their own phones, dialing doctors directly and switching networks repeatedly until a call finally goes through.

“In cases like labour when we need a doctor, we use our phones to call the assigned telemedicine doctor, Dr. Tony Ezeanya, after taking the patient’s history. Even at that, we may have to change SIM cards for strong network coverage,” she said.

Scenarios like this play out across many rural parts of Anambra State, where telemedicine was introduced as a response to shortages of doctors and delays in emergency care at primary healthcare centres. For frontline health workers, the programme raised expectations that distance and limited staffing would no longer determine whether patients receive timely medical attention.

But in many rural facilities visited, the reality has been more complicated, with basic challenges such poor network coverage, poor people’s perception, and power supply limiting how often the system works in reality. They wonder why you who have been attending to them all these years suddenly depend on another person they are not seeing to manage their conditions.

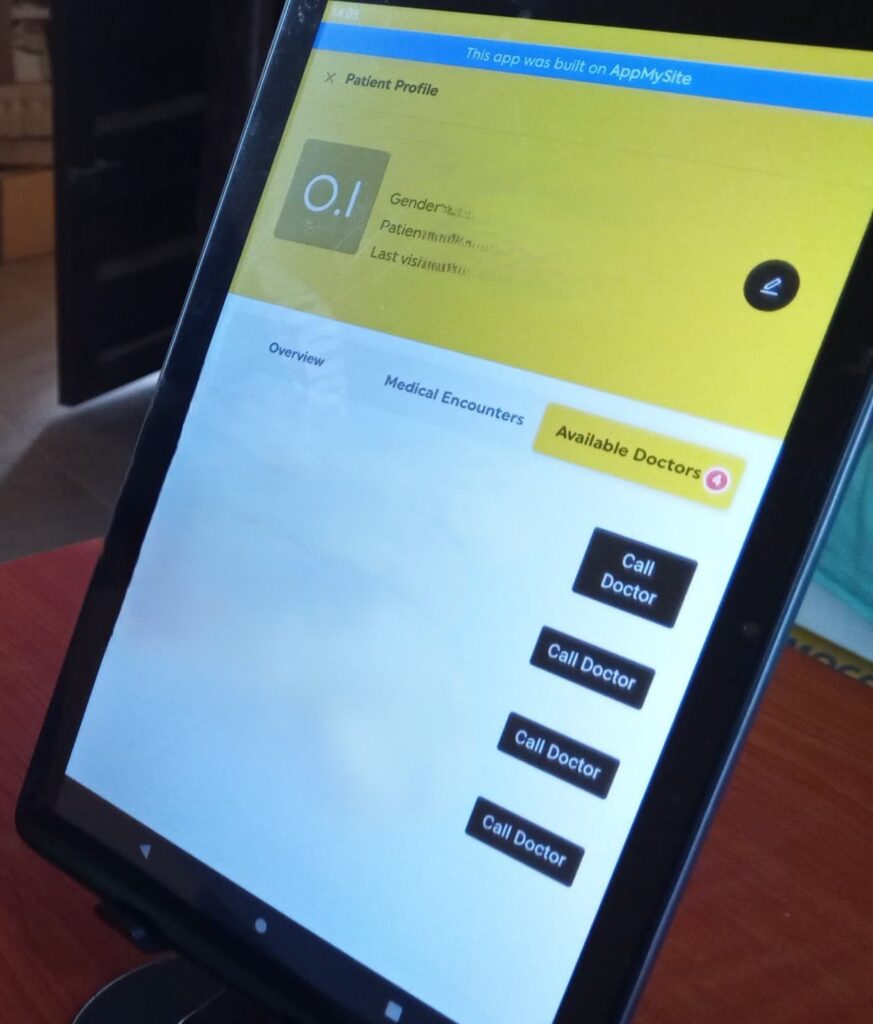

The state government launched the telemedicine initiative in November 2024 to improve access to quality healthcare services, particularly maternal and child health, across 329 primary healthcare centres enrolled under the Basic Health Care Provision Fund (BHCPF). The initiative was designed to increase efficiency by enabling nurses and community health officers to consult doctors remotely when cases exceed their capacity.

Explaining the policy in his recent comments, the Commissioner for Health, Dr Afam Obidike, said the programme was meant to address gaps in human resources at the primary healthcare level. Under the model, telemedicine hubs were established in each of the state’s 21 local government areas, with doctors available to support ward-level facilities through digital consultations.

When the telemedicine initiative was introduced, early reporting captured a wave of optimism around its potential to change how care is delivered at the primary level. In a previous report published shortly after the launch, health workers and government officials spoke of the programme as a breakthrough that would ease long-standing pressure on rural facilities and expand access to specialist support across the state. At the time, it was framed as a shift that could narrow the gap between urban and rural healthcare delivery.

However, one year after its introduction findings from visits to primary healthcare centres show that the programme’s impact depends largely on local conditions that remain uneven across the state.

When the network fails, the system falters

In many rural Primary Healthcare Centres (PHCs) visited across Anambra, the success of telemedicine depends largely on whether a phone call can go through than an actual medical diagnosis or treatment. Officers-in-Charge of PHCs who spoke with this reporter said unstable mobile networks routinely disrupt consultations, forcing them to abandon the state-provided devices and rely on personal phones.

In Amansea, Awka North LGA, the OIC, Eunice Obi, who lauded the programme lamented that network interruptions often cut calls mid-consultation. She explained that patients grow impatient when calls drop repeatedly, especially when they are referred to unseen doctors after years of being treated directly by nurses at the facility.

“Sometimes, you are on call with the doctor for a critical case, the network drops and the call is aborted. It wastes patients’ time and I see it on their faces.”

Ogolor, in Umudora PHC, said the telemedicine gadget supplied to the facility is largely unusable because of poor network coverage. According to her, unreliable signal makes it impossible to place calls through the device during emergencies. When serious cases present, she said health workers switch between SIM cards on their personal phones, searching for any available signal.

In Umueze-Anam 1 Primary Healthcare Centre in Anambra West, the OIC, Emmanuella Anyanwu, said poor mobile coverage means consultations rarely happen at the first dial. She explained that when a doctor cannot be reached immediately, she monitors network strength on her personal phone before calling to explain the patient’s condition sometimes when the patient must have left. Video consultations is usually a no-go area due to poor network, she added.

“In Umueze-Anam and most parts of Anambra West, network coverage is very poor. Calls hardly go through. When we cannot reach the doctor, I keep checking my phone. The moment the network improves, I call and explain the situation so the doctor can guide us on the next steps.”

These disruptions have direct consequences on patients. In Ogbaru LGA, Ifeoma Ndu, OIC of Ogbakuba PHC, recalled a case involving a man with a heart condition. She said repeated attempts to reach the telemedicine doctor failed, forcing her to refer the patient to another facility.

“The family refused to travel at night due to insecurity. When the doctor eventually returned my calls, he told me to refer them the patient. But it was too late, the patient died early around 4.00 am the next day despite our efforts.”

In many villages, the absence of stable network coverage remains the single biggest obstacle to consistent telemedicine use, turning a digital health solution into an uneven and unreliable service.

For some health workers, poor connectivity comes at a cost. Several officers said ₦20,000 is deducted monthly from their facilities’ quarterly BHCPF disbursements for data subscriptions that often expire unused because network access is unreliable. They said they are warned not to use the data for purposes outside telemedicine, even when it cannot function as intended.

A Ward Development Committee Chairperson, Ogoamaka Atuenyi confirmed this. “I don’t like the idea of government collecting N20,000 from the facility. The quarterly disbursement is not even enough. All these deductions reduce the value of the money.”

While some officers manage by hot-spotting personal data from alternative networks, they say the telemedicine gadgets only functions outside their communities where signal strength improves.

“Since one network is unreliable both on personal devices and telemedicine tablet, I often hotspot internet with my other network to connect the telemedicine device. The data provided through the programme only works when I move out of the community to where there is better network coverage,” Joy Enweremadu explained.

Patients don’t trust what they can’t see

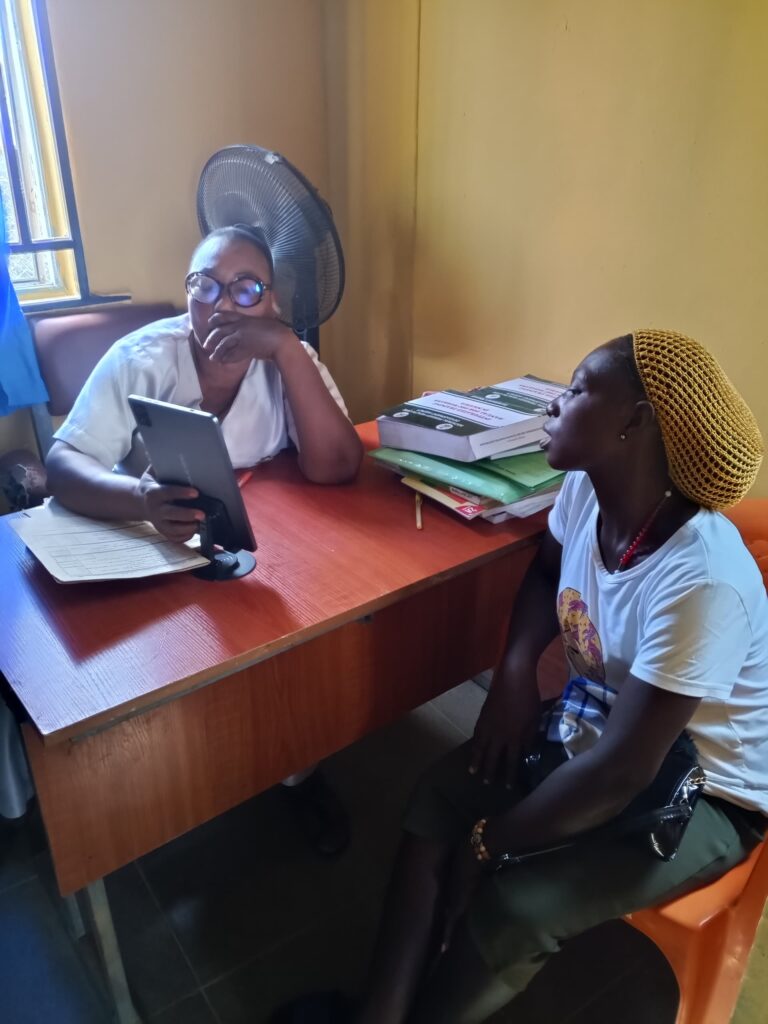

Beyond technical challenges, health workers disclosed that community perception is quietly shaping how telemedicine is received.

According to them, many rural dwellers see health workers taking advantage of telemedicine as a sign of incompetence or inability to take initiative.

“For those of them who know you, they look at you like – what is happening to you that you now need to consult over the phone before attending to them,” OIC Eunice Obi said.

Interactions with rural residents appear to support this view.

Roseline Nwoye, a resident of Amansea, Awka North LGA, said her initial reaction was one of doubt. “When I notice she was calling a doctor, my first impression is that she does not know what she is doing.”

Nwoye’s reaction is not unusual. Chioma Ajie, a young lady in her thirties receiving care at Akili-Ozizor PHC, said she was initially uncomfortable with the idea of her case being discussed over the phone.

“I couldn’t understand why she would do that when I needed urgent treatment. The OIC took some time to explain things to me. Otherwise, I feel it was time wasting.”

Chinyere Okafor-Ogugua, a resident of Igbakwu in Ayamelum LGA, shared similar sentiment.

“The perception is widespread that the nurses do not understand what they are doing. However, with my personal level of exposure, I understand that government is leveraging technology implementing such a programme.

Health managers acknowledge that the perception problem is real and persistent. Mary Onwuegbuka, Director of Primary Healthcare in Ogbaru LGA and a former OIC, said patients often expect immediate treatment and grow impatient when referrals or consultations are introduced.

“It’s true, you tell patients you want to call a doctor, they look at you as if you do not know your job. They say, ‘Treat me and let me go.’

“That is why they prefer to go to a chemist where they receive the drugs immediately. So, they do not understand why tests or referrals are required. When doctors request laboratory tests or X-rays through telemedicine, it becomes difficult.”

To navigate this challenge, some OICs have begun adopting informal coping strategies to maintain patient trust. Joy Enweremadu, OIC at Akili-Ozizor PHC, said she often initiates basic first aid before stepping aside to consult a doctor.

“That is due to their perception that the matron does not know what she is doing if she has to call a doctor before treatment. This affects trust.

Doctors on the line, but not always available

Some health workers said the challenge with telemedicine goes beyond poor network coverage to delays in getting timely responses from doctors on the other end of the line. This fuels the suspicion that the doctor might be combining the telemedicine engagement with other responsibilities.

In emergency situations, such delays can be deeply unsettling for frontline health workers who rely on prompt guidance to manage critical cases.

“I feel so tense calling for assistance while doctors are not picking calls, but they are human beings who have other things to do,” said Lauretta Nwoye, Officer-in-Charge of Ugbenu PHC in Awka North LGA.

Another OIC in Awka North expressed similar concerns, suggesting that uneven responsiveness among doctors affects confidence in the system. “Out of the two in our LGA, I call one of them because he is always there. The second one does not pick calls and does not call you back.”

This experience echoes an earlier account by Ndu, the OIC of Ogbakuba PHC in Ogbaru LGA, who said she had repeatedly tried to reach a telemedicine doctor without success. “He called back when he saw my missed calls,” she said.

Health workers say such experiences contribute to skepticism and lukewarm attitudes toward the programme among both providers and patients.

In response, the Director of Primary Healthcare in Ogbaru LGA, Mary Onwuegbuka urged frontline workers not to abandon the initiative despite its challenges.

“Before I was made the Director of PHC, if I call the doctors for our LGA and I don’t get them, I call any of those from other LGAs just to ensure that I get result.”

Beyond responsiveness, some OICs pointed to community lifestyle patterns as another barrier to effective telemedicine use. Joy Enweremadu, OIC of Akili-Ozizor PHC in Ogbaru LGA, noted that patients often arrive at health facilities late in the day.

“They go to their farms in the morning and visit the health facility in the evening, when doctors are no longer online.”

Enweremadu shared view by many OICs interviewed by Radio Nigeria that periodic physical visits by doctors could strengthen the programme’s impact and improve community trust.

“When villagers know that a doctor will visit on a particular day, they are more encouraged to come to the facility. That would improve community trust and acceptance. On days when the doctor is not physically present, telemedicine can then be used more effectively.”

No ambulance for referral

When telemedicine needs strong referral system for greater efficiency, another set of problems quickly emerge. The death of a patient earlier recounted by Ndu, OIC Ogbakuba PHC is a testament to the unfortunate reality.

“After consulting the doctor, he told me to refer the man but they refused to go because it was too late in the night and our place is not safe.”

While the death cannot be attributed directly to the telemedicine programme, it exposes the limits of remote consultation in communities where referral systems are weak and insecurity makes emergency movement risky or impossible.

“We do not have an ambulance to convey them and no tricycle or vehicle driver would agree to risk going out that night,” Ndu lamented.

In hard-to-reach and insecure areas like parts of Ogbaru, the absence of ambulances, coordinated transport arrangements, and protected referral pathways means that clinical decisions made through telemedicine often cannot be acted upon. As a result, health workers are left to manage critical cases beyond the limits of their facilities, not due to negligence, but because the systems meant to support escalation of care are either weak or unavailable when they are most needed.

The Director of Primary Health Care in Ogbaru LGA, Mary Onwuegbuka, also acknowledged how insecurity undermines referrals, even as she encouraged health workers to continue engaging with the state’s telemedicine initiative.

“For emergency response, we were advised to keep phone numbers of local transporters, but insecurity in some communities makes night movement difficult.

“If you call them during night hours here in Ogbaru, they often refuse to come out due to insecurity,” she said.

Telemedicine helps but not enough

Medical professionals interviewed by this reporter extolled the telemedicine programme which they agreed fills a gap in the health system long bedeviled by manpower shortage. For them, the telemedicine programme has value but it cannot stand on its own.

Oluebube Agba, one of the telemedicine doctors supporting facilities in Anaocha LGA, described the initiative as a significant shift in how primary healthcare is delivered. He said the platform has enabled doctors to intervene in cases that frontline health workers would ordinarily consider difficult to manage.

“I have used it to manage many cases PHC workers consider very complex. I remotely guided the OICs or her staff to manage them better without casualty.”

However, an Anambra-based medical practitioner, Dr Gideon Obiasor, cautioned that telemedicine should function strictly as a support system rather than a substitute for physical medical care.

“Telemedicine is a welcome development, but it can never replace physical medical care. We should accept and grow with it despite all the challenges.”

On the growing demand for physical visits by doctors, Obiasor argued that current realities may soon make such expectations unsustainable.

“A time will come when physical visits will no longer be feasible due to the doctor-to-patient ratio we currently have. Doctors who are motivated to remain in the country after graduation are not enough. This is already a national crisis.”

He said for telemedicine to function effectively, the underlying infrastructure must be addressed.

“Telemedicine cannot work if devices, connectivity and infrastructure are constantly down due to lack of electricity. Government must provide alternative power sources such as solar power.”

Obiasor also pointed to the need for more reliable connectivity beyond conventional mobile networks.

“With political will, government can install Starlink or other alternatives in communities to connect telemedicine endpoints. These do not depend on conventional networks like MTN and can work anywhere.

“Although it is costly, it is something that can be funded and deployed, at least at central locations within rural communities. On the whole, systemic issues must first be addressed,” he said.

Government reactions and ground reality

Responding to the concerns raised, the Commissioner for Health, Dr Afam Obidike, said the state government was addressing the challenges around connectivity and telemedicine infrastructure. He said fibre optic expansion was ongoing across Anambra.

“There is hardly any place in Anambra where you cannot browse, even though people may have to choose which network works best for them.

“Telemedicine is not restricted to one network. It works with internet and Wi-Fi. Any network that is stronger in a particular area can be used,” he said.

Obidike added that health workers could also rely on their personal phones to reach consultants.

“Health workers can still call consultants directly with their phones. It is still part of the telemedicine system.”

He, however, accused some health workers of bypassing the system.

“But while we sincerely acknowledge most health workers for helping us at the primary healthcare level, some of them bypass telemedicine and refer patients to private doctors for personal benefits.”

On referrals and emergency response, the commissioner said the state had ambulances stationed at Umueri and Anaku General Hospitals, with four more to be deployed.

“We have almost 29 private hospitals that have registered under our Emergency Medical Service and Ambulance System. In Anambra West, we are about to complete the construction of the first general hospital. It will also have ambulances. These are all to further strengthen the referral system.

“So, anywhere you are in Anambra, dial 5111 and request for an ambulance, they will come. There is nowhere you cannot drive to in Anambra State,” he said.

However, findings from this investigation show that access remains a challenge in several communities, particularly in parts of Awka North, Anambra West and Anambra East LGAs. Areas such as Umudora-Anam, Oramaetiti-Anam, Ukwuala and Innoma in Anambra West still struggle with poor road conditions, limiting emergency movement despite ongoing road construction across the state.

On manpower, Obidike acknowledged that shortages were a national problem but said Anambra was responding within its capacity.

“We have recruited nearly 1,000 healthcare workers under Governor Chukwuma Soludo and will soon assign 3,000 community-based health workers. We are going to recruit again.”

He said government policy targets at least one fully functional primary healthcare centre operating 24 hours in each ward.

“Our administration has worked to ensure that at least one is fully functional in each ward. When you see any one of such not fully operational, just alert me immediately and I will take prompt action.”

Addressing resistance to telemedicine and electronic health records, Obidike attributed it partly to staff accountability concerns.

“Some people do not want to be monitored by authorities, including beneficiaries of previous improper recruitment. We are planning staff verification next year to weed out some who are dragging us back,” he said.

Anambra State ICT Agency speaks

When contacted over complaints of poor internet connectivity, the Managing Director of the Anambra State ICT Agency, Chukwuemeka Fred Agbata, spoke with this reporter by phone on Sunday, December 14, 2025, and requested that the questions be sent to him via WhatsApp. The questions were subsequently sent, seeking clarification on the ICT Agency’s role in supporting the telemedicine programme, efforts to improve internet connectivity in rural communities, concerns about network limitations affecting telemedicine operations, and plans for further expansion of digital health infrastructure in 2026.

As at December 16, 2025, no response had been received. A follow-up call placed to him was not answered. His agency’s Communications Desk later indicated that responses were still being prepared, but none was provided as of the time of filing this report.

However, findings revealed that the ICT Agency plays a largely behind-the-scenes role in the telemedicine programme. Its responsibility is to build and host the digital platform, while working with the Ministry of Health to train health workers and support the technical side of operations.

To improve internet access across the state, the government waived a long-standing barrier that slowed network expansion. Anambra abolished Right of Way (RoW) charges, which previously required telecom companies to pay fees for every metre of fibre cable laid. By removing these charges, telecom operators are now able to extend broadband infrastructure more easily and at lower cost.

In previous interviews, the ICT Agency said the waiver is already helping to expand broadband coverage, strengthen digital capacity and lay the foundation for improved connectivity across the state. However, those promised gains feels too distant for officers-in-charge (OICs) who still struggle to place a stable call during emergencies, and patients whose care depends on that connection.

This report was made possible with support from the International Centre for Investigative Reporting, (ICIR) under its Strengthening Public Accountability For Results and Knowledge SPARK 2 project.