By Bilkis Abdulraheem Lawal

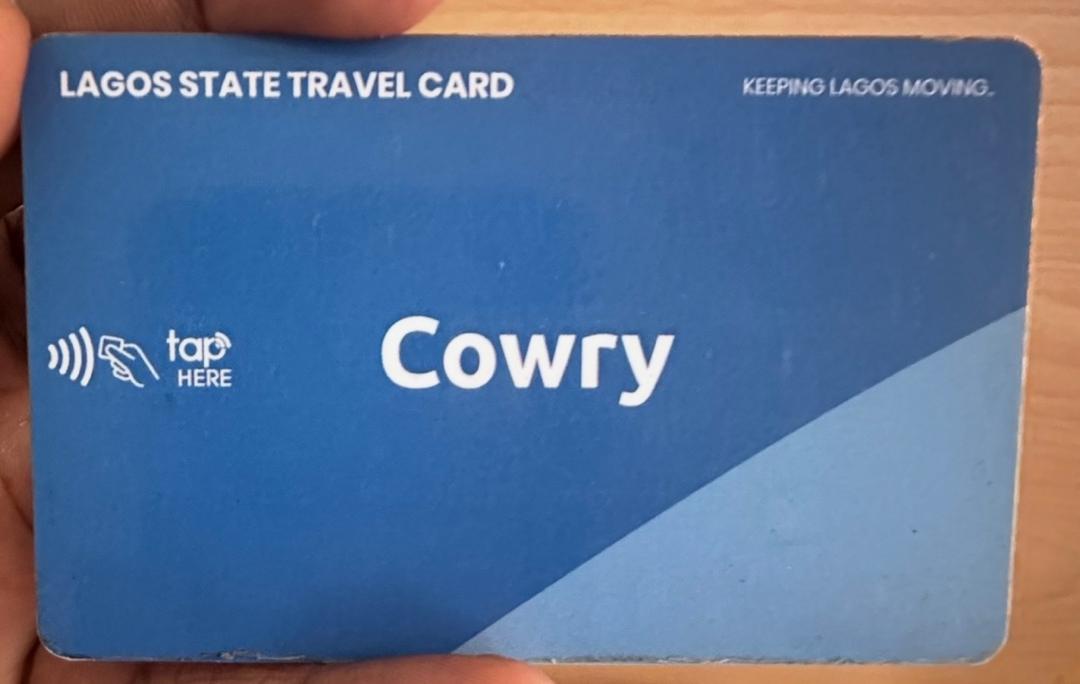

(Cowry Card. Photo Credit: Bilkis Abdulraheem Lawal)

When the Lagos State Government introduced the Cowry Card in August 2020, it was presented as more than a fare payment tool. It was framed as a governance intervention, one designed to eliminate cash handling, reduce fraud, close revenue leakages, and bring transparency to a historically opaque public transport system.

By February 1, 2021, the Lagos State Metropolitan Area Transport Authority (LAMATA) had enforced the Cowry Card as the sole payment method on all Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) buses, effectively ending the paper ticket era.

Today, the Cowry Card is now used across Lagos state transport services operated by companies such as Primero Transport Services Limited, Lagos Bus Services Limited, Amalgamated Transport Services Limited, TJ Motors, and Transport Services Limited. Its use has expanded beyond buses to include the Lagos Ferry Services (LAGFERRY) and the Lagos Rail Mass Transit Blue and Red Lines.

Powered by Touch and Pay Technologies (TAP), the Cowry Card sits at the intersection of identity payments, and data – the three core components of Nigeria’s emerging digital public infrastructure DPI). Linked to commuters’ phone numbers which is tied to their National Identification Number (NIN), the system promises traceability, interoperability, and accountability in the delivery of public transport services.

Yet, as commuter testimonies and on-ground observations show, the transition to a cashless transport system has delivered both measurable gains and unresolved enforcement gaps.

How the Cowry Card Works

LAMATA spokesperson, Kolawole Ojelabi, explained that commuters purchase the Cowry Card for ₦500 at major BRT terminals and register it by linking it to a phone number – in Nigeria Sim-NIN linkage is mandatory prerequisite to having a mobile number. Registration can be completed at the point of purchase or through the Cowry mobile application.

Once registered, users can fund the card through the Cowry App, authorised terminal agents, or supported banking applications.

Balances can be checked via the Cowry App or through authorised agents.

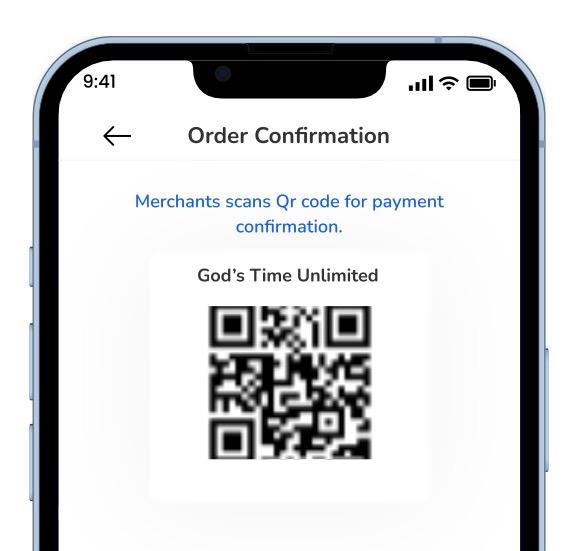

To accommodate users who forget their physical cards, commuters can use the Cowry App to generate a digital ticket by scanning QR codes displayed on buses or stations.

Commuters’ Experiences

For many users, the Cowry Card represents a clear improvement over the paper ticket system.

Sodeinde Sonaike said that whenever he recharges his Cowry Card, he asks agents to confirm his balance, noting that the system saves time compared to the long queues that characterised the paper ticket era. According to him, the card has reduced delays and improved predictability in daily commuting.

Faoziya Abdullah said she prefers the card because it allows her to load transport funds for an entire month once she receives her salary. As a daily commuter, she said the system makes her journey to work smooth and stress-free.

Others highlighted transparency. Oluwadamilola Adeleye said she usually recharges her card with the exact amount needed for her transport fare and has never experienced unexplained deductions or accumulated debt.

Segun Babalola echoed this view, describing the Cowry Card as “easier and more transparent” than paper tickets. He attributed his positive experience to consistently tapping in and out at the start and end of each trip. Although he said most of their drivers are professionals, there are some bad eggs among them who sometimes can be reckless.

Frank Otabor, a new BRT user, said the Cowry Card has simplified his commute, noting that its integration across buses, trains, and ferries enhances mobility. Beyond designated lanes that reduce travel time, he described the card as “a beautiful experience.”

Where the Cracks Appear

Despite these gains, commuter experiences also point to gaps between policy and practice.

Adeleye observed that some shuttle buses still collect cash from passengers without Cowry Cards, an action that directly contradicts LAMATA’s cashless policy. She urged authorities to “investigate and take the necessary action to block this loophole.”

This raises a central accountability question: if the Cowry Card is mandatory, how does cash continue to circulate within parts of the system, and who benefits from these informal transactions?

Security, Surveillance, and Responsibility in a DPI System

LAMATA spokesperson, Kolawole Ojelabi said the Cowry Card operates with multiple layers of protection embedded within Nigeria’s digital public infrastructure. He explained that linking cards to NIN-backed phone numbers provides an added layer of traceability.

He advised commuters to report lost cards immediately so they can be blocked and balances transferred. According to him, this is critical because the card is registered to an individual’s phone number, and misuse, including criminal activity, could be traced back to the registered owner.

The system, he added, operates under Nigeria’s financial regulatory framework, with oversight from the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN). Transactions pass through switching companies such as the Nigeria Inter-Bank Settlement System (NIBSS) and e-Tranzact, which handle reconciliation and remittance to transport operators.

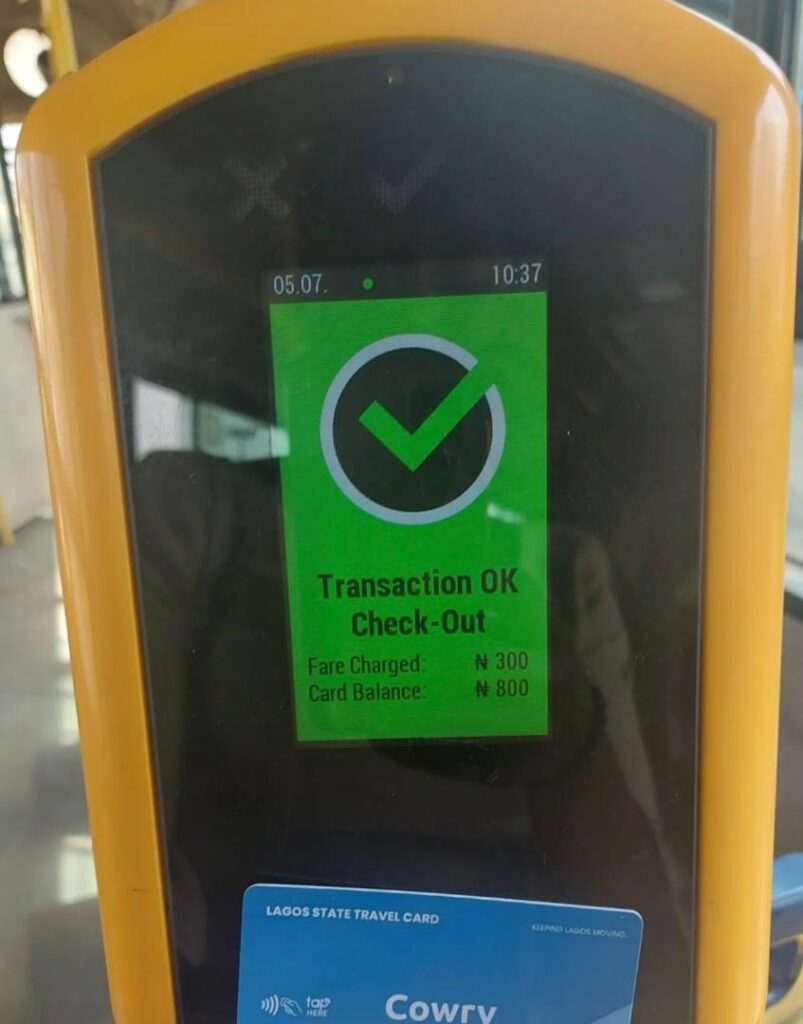

On complaints of over-deduction, Ojelabi attributed most cases to commuters failing to tap out. However, he acknowledged that network failures can also cause errors. Affected users, he said, can lodge complaints via phone or email, after which refunds are processed following verification.

Enforcement, Trust, and the Limits of Technology

LAMATA says enforcement mechanisms exist. Ojelabi urged commuters to report drivers who collect cash or engage in misconduct by submitting the vehicle number plate and identification code displayed on buses. According to him, the agency can track who, when and where violations occur, and several drivers have been removed from the system.

Yet for commuters, the persistence of cash collection raises broader questions about consistency, monitoring, and trust. As with many digital governance systems, technology can record behaviour, but only strong enforcement can change it.

A Model Under Scrutiny—and Replication

Ojelabi disclosed that several states have visited Lagos to study LAMATA’s transport model with the intention of replicating it. He advised states like Oyo that has started replicating the transport model to establish bus stops spaced between 200 and 500 metres, engage stakeholders early, and prepare for possible displacement caused by infrastructure expansion, adding that the Lagos State Government compensates affected landlords and tenants.

While the Cowry Card system is increasingly positioned as a national model, commuter experiences suggest that its success depends not only on digital infrastructure, but on sustained enforcement, transparency, and responsiveness to public complaints.

As Lagos deepens its reliance on digital systems to govern mobility, the Cowry Card stands as both a symbol of progress and a test case for Nigeria’s Digital Public Infrastructure. It shows how payments, identity, and data can be combined to improve public services and how gaps in enforcement can undermine those gains.

This report is produced under the DPI Africa Journalism Fellowship Programme of the Media Foundation for West Africa and Co-Develop